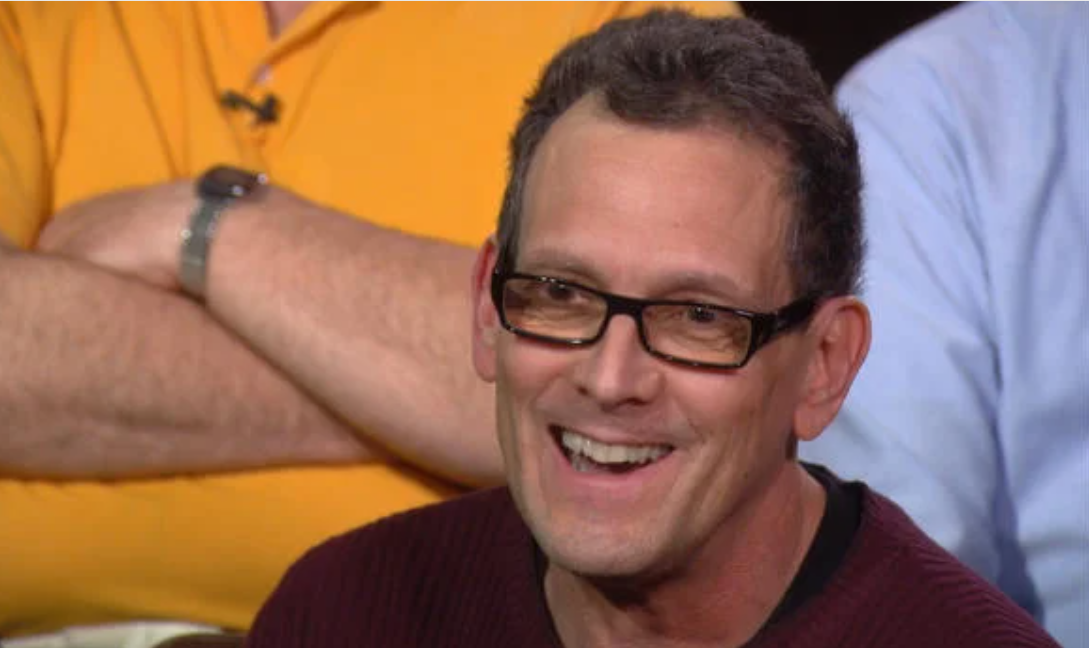

It’s very rare to see people like Bob Petrella—a man whose memory spans decades in near-photographic detail. Every date, nearly every day of his life since early childhood, lives somewhere inside him. He remembers it all.

In this article, we will explore Bob Petrella’s life, how his brain preserves what most of us forget, and reflect on what such a rare gift reveals about memory, identity, and what it means to live with the past.

Early Life and the Discovery of a Rare Memory

Bob Petrella grew up in western Pennsylvania and later made his home in Los Angeles. From childhood he displayed a knack for remembering — not just facts or school lessons, but days, conversations, experiences. As he told interviewers, he passed many tests in primary school without ever studying. He didn’t realise his difference was exceptional; to him, remembering was simply normal.

Only later, when scientists studying memory began to reach out to individuals claiming unusual recall abilities, did Bob’s life become of broader interest. In 2008 he became the fourth person known to be diagnosed with Hyperthymesia (also called Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory, or HSAM) — a condition that allows people to recall personal events with exceptional clarity.

From then on Bob Petrella would no longer be an ordinary man with a strong memory. He became a living archive.

What It Means to Live With HSAM

HSAM is rare. Fewer than a hundred people worldwide have been identified as hyperthymesiacs. The condition differs from what we usually call “photographic memory” or “memory champions.” People with HSAM do not necessarily do better than average on memory tests involving lists, numbers, or abstract material — their gift lies in autobiographical recall: recollecting personal experiences, places, dates, emotions, and contexts.

For Bob Petrella, this means that given nearly any date — past or present — he can often tell you where he was, what he was doing, sometimes even what he ate or how he felt. He remembers birthdays and New Year Eves, childhood events, early relationships, everyday details. According to media reports, he can recall “up to half” the days of his life in vivid detail.

In an interview referenced by researchers, Petrella described using his memory almost casually. If stuck in traffic, he might scroll through memories of that date, selecting “the best Saturdays in June” from among decades of summers.

Some days seem special enough to become mental bookmarks; other days carry only quiet background noise. But the capacity to access those layers at will — to travel backwards in time in a single mind — remains remarkable.

Memory Under the Microscope: What Science Has Learned

When Bob agreed to participate in memory studies at University of California, Irvine (UCI), researchers led by James McGaugh sought to examine what sets hyperthymesiacs apart. They administered standard tests — word lists, number sequences — where Petrella and his peers scored no better than average.

But when the tests focused on autobiographical recall or public-event timelines — for example: “What day of the week was January 1, 1984?” — these HSAM individuals performed at levels far beyond ordinary capacity. Petrella answered correctly; he also recalled that his favorite sports team, the Pittsburgh Steelers, lost that day.

Brain scans revealed structural differences as well. Some regions involved in memory storage and retrieval — areas tied to encoding personal experiences, emotional associations, and contextual details — appeared altered compared to controls. Among these was the caudate nucleus, a brain area sometimes linked to repetitive behavior and obsessive-compulsive traits.

Researchers propose that HSAM may not stem from magical memory storage. Instead it may reflect a combination of unusual brain wiring and habitual habits: frequent mental rehearsing of past events, perhaps obsessive reflection, and a life spent revisiting memory. In other people, forgetting may serve as mental housekeeping. For hyperthymesiacs, forgetting separates them from the burden — or gift — of total recall.

Life Beyond Memory: The Upsides and the Weight

Having a memory like Bob’s is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it offers a continuity many people lose: childhood days, high school friendships, first loves, old fears, early hopes — all remain accessible. On the other hand, an inability to forget means every loss, every regret, every scratch of pain remains part of you forever.

Petrella has admitted this — in some cases, the memories are vivid not because they were pleasant, but precisely because they were painful or emotionally heavy. The burden of grief, loss or regret remains fresh whenever he revisits those days in his mind.

At age 50, Bob created what he calls the “Book of Bob.” For each calendar day of the year, he selected one of his most memorable experiences — a kind of scrapbook of memory, mental and written. These entries include the spectacular and the mundane. Some recall love or laughter; others carry shadows and hardship.

Bob also carries within him an imaginary world. In one public interview, he described a made-up college basketball team — the Holland College Golden Knights — a team, league, history of decades he created in his mind, and continues to replay with full detail. Starting at age 13, he envisioned them competing, winning championships, graduating players, suffering injuries. To him, the history is as real as memories of actual friends.

Scientists studying him describe this not as an illness, but as a rare wiring of the mind: ordinary in all other aspects, but equipped with a mental archive that defies time.

Memory as Time Machine

For most of us, memory is fragile. Time softens focus, erodes detail, layers emotion over events. Memory becomes subjective — shaped by shifting perspective, altered by what we choose to remember or forget. For Bob, memory offers consistency. Dates, emotions, events — they all stay preserved, perhaps darker or more luminous than day one.

That raises a question: how much of our identity depends on forgetting? For most people, forgetting is a part of growth. It allows wounds to heal, regrets to fade, versions of ourselves to evolve. In contrast, hyperthymesiacs live tethered to all versions of themselves, constantly aware of every step, every misstep, every moment.

Memory and Emotional Weight

With total recall comes emotional weight. Joys remain joyful; trauma remains painful. Pain doesn’t dull with distance when your memory tirelessly preserves every detail. Bob Petrella’s memories of youthful pleasures may bring delight, but memories of loss or heartbreak come with equal clarity and permanence.

In that sense, forgetting becomes more than a flaw: it may be a grace. A protective filter that allows people to move on, to evolve, to put distance between past and present. For Bob, there is no such distance.

Science sees in Bob Petrella and others like him a chance to understand memory differently. Their cases show that memory is not a single faculty; it consists of systems — episodic memory, emotional memory, procedural memory, semantic memory, and more. HSAM seems to enhance just one: the autobiographical, episodic memory tied to personal experience and time.

Meanwhile, other types of memory — remembering a grocery list, string of numbers, or random facts — remain ordinary, or even unremarkable. That suggests memory’s complexity. It underscores how human cognition divides tasks and how unique wiring can transform ordinary life into something extraordinary.

Many hyperthymesiacs describe their memory as both gift and burden. The ability to remember is alluring: how many of us wish we could recall childhood summers, long-forgotten birthdays, or faces from decades ago? But at what cost? Emotional pain, loss, regret — they carry the same permanence.

Bob Petrella’s story shows us memory’s complexity: it is not just about recollection, but about balance. Forgetting may often be necessary for living. Remembering, when forced without choice, can shape life in ways most of us never imagine.