Cappadocia can be found in the heart of Central Anatolia. It holds a landscape that seems shaped by an unseen hand. It rises and folds in soft ridges, valleys, and cones, its volcanic formations worn smooth by wind and time. Visitors often describe the region as dreamlike, with tall stone pillars standing like guardians and whole hillsides carved into chambers. Yet the scene is not only a marvel of nature. For thousands of years, entire communities carved out their existence beneath this terrain, living in vast underground settlements that stretched for miles beneath the earth.

The people often called the “cave dwellers” of Cappadocia did not choose subterranean life because of mystery or ritual. Their existence below ground grew from a need for safety, climate control, and shared survival in a land that offered both abundance and danger. Over centuries, they built cities with stables, homes, schools, churches, cisterns, and ventilation towers, all hidden beneath the surface. Some complexes reached more than eight levels deep and held thousands of residents. In this part of Turkey, the earth itself became a shelter, a fortress, and a home.

Origins in Stone: A Landscape Made for Shelter

Cappadocia’s unusual terrain was created long before humans walked its valleys. Millions of years ago, volcanoes such as Mount Erciyes, Mount Hasan, and Güllü Dağ spread thick layers of ash across the region. Over time, the ash hardened into tuff, a soft rock that shapes easily when carved yet remains sturdy once finished. Rain and wind sculpted the surface into the fairy chimneys and cliffs seen today. For early settlers, this landscape offered ready-made protection and a natural canvas.

Archaeological evidence shows that people in the region carved simple caves as early as the Iron Age. These first chambers were small refuges, used mainly as storage spaces or shelters from harsh weather. As populations grew and power shifted between empires, groups sought places to hide during raids and political turbulence. The caves soon turned into tunnel systems, and before long, whole underground districts took shape.

Cappadocia never held a single tribe in the traditional sense, but rather a succession of cultures that relied on the underground world for safety. Over hundreds of years, Hittites, Phrygians, Romans, early Christians, Byzantines, and Seljuk Turks all shaped these settlements. What many call the “cave-dwelling tribe” is therefore a blend of communities whose lives intertwined through the generations.

Among the most impressive underground complexes are Derinkuyu and Kaymakli. They reveal how advanced the engineering of these communities became.

Derinkuyu, the largest known underground city in the region, could reach a depth of about 18 stories. It contained storage rooms, wells, kitchens, a school, meeting halls, and even a winery. Narrow tunnels linked one level to another, while thick stone doors rolled across entrances to seal off entire sections in times of danger.

Archaeologists believe Derinkuyu could shelter between twenty and fifty thousand people for extended periods. Families lived in multiroom chambers carved with careful precision. Animals were kept in underground stables, and large communal spaces served for worship and gatherings. The soft rock allowed builders to create rounded ceilings, long corridors, and vents that carried air from the surface down to the lowest levels. These features kept temperatures cool in summer and mild in winter.

Kaymakli: A Subterranean Network of Homes and Workshops

Kaymakli, located near Derinkuyu, stretches across many layers of tunnels and chambers. It is known for its ventilation system, which many researchers consider one of the most sophisticated of the ancient world. Residents organized the city into sections for storage, residential life, and craft work. Small recesses and shelves built into the walls show where lamps, tools, and food were kept.

The two cities were once connected through long tunnels, suggesting that underground life operated like a shared network rather than isolated pockets. When threats appeared on the surface, thousands of people could move into the earth, sealing themselves into a world designed for secrecy and survival.

Life Below the Surface: Community, Craft, and Tradition

Daily life underground required adaptation, but it also delivered a sense of shared protection. The underground cities offered a controlled environment where temperatures remained stable, food could be kept longer, and water sources were safe from contamination or attack.

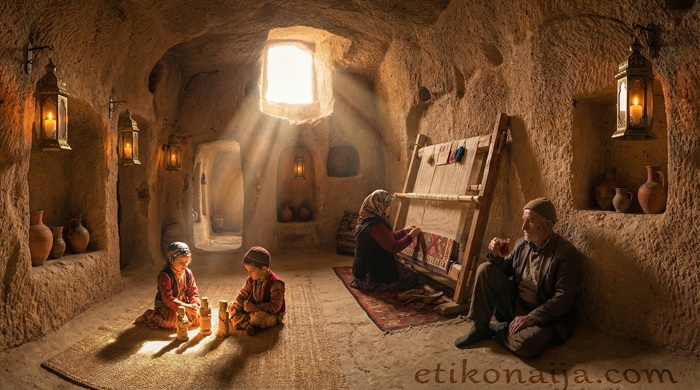

Families lived in connected rooms clustered around shared spaces. Carved platforms served as seating or sleeping areas. Narrow corridors separated sections of the city, allowing residents to maintain privacy while remaining part of a larger community.

Even underground, craftsmanship thrived. Residents produced pottery, textiles, metal tools, and stone carvings. Some rooms served as workshops, complete with niches for storage and ventilation openings to remove smoke from fires used in metalwork.

As life stabilized across centuries, many families spent only part of the year underground, choosing to farm or trade above ground during peaceful seasons. The underground cities functioned as both permanent homes and safe retreats—a dual purpose that endured well into the medieval era.

Religion and Learning

Cappadocia played a central role in early Christian history. Many underground chambers served as churches adorned with simple frescoes, arches, and domed ceilings. Chalk crosses carved near entrances identified sacred areas. Children learned reading and writing in underground schools, where lessons continued even during difficult years.

Food Storage and Preservation

Large storage jars preserved grains, beans, dried fruit, and wine. Underground kitchens used controlled ventilation to remove smoke while keeping heat within the rock. The natural insulation allowed food supplies to last through long winters or extended periods of hiding.

Wells and cisterns ensured clean water for thousands of residents. Some wells connected to natural aquifers that outsiders could not reach. The ventilation system, designed through tall shafts that rose to the surface, kept the air fresh and circulated throughout the city.

These innovations reveal a way of life built on careful observation of the environment and a deep respect for shared survival.

Why Underground Life Became Necessary

Throughout its history, Cappadocia lay between powerful empires. The region witnessed frequent conflict, invasions, and migration. Underground cities became a defense strategy during periods of political instability.

From the Hittite period to the Byzantine era, the area faced raids from rival groups. Underground settlements allowed entire communities to disappear from the landscape within minutes. Entrances were few and hidden, sometimes concealed beneath barns or rocks. Massive stone doors, which could only be opened from the inside, ensured that intruders could not enter.

In the early centuries of Christianity, believers sought safe places to practice their faith away from persecution. Cappadocia’s caves provided sanctuary, allowing communities to gather, worship, and teach without fear.

Even during the Seljuk and Ottoman periods, underground cities continued to serve as emergency refuges. Although the surface world became safer over time, communities preserved the underground systems as a cultural inheritance and protective measure.

The underground environment became a long-term strategy for resilience in a region shaped by shifting borders and political realities.

Cappadocia’s cave dwellers did not consider themselves separate from the natural world. Their architecture flowed with the curves of the terrain. Their traditions respected both the land above and the networks below.

Stonework formed the heart of their creative expression. Soft tuff allowed craftspeople to produce smooth walls, ornate facades, and hidden chambers. In some villages, families carved dove houses into cliffs, raising birds whose droppings enriched nearby farms.

Agriculture filled the months of spring and summer. Wheat, grapes, apples, and apricots thrived on the fertile volcanic soil. During cold winters, communities stayed close to the caves, where temperatures held steady.

Living underground required cooperation. Families shared resources, protected each other during emergencies, and taught skills from one generation to the next. This shared life shaped a culture centered on trust, resilience, and practical knowledge.

Cappadocia Today: A Living Heritage

Although most residents now live above ground in towns such as Göreme, Ürgüp, and Uçhisar, the underground cities remain a source of local pride. Many families still use carved homes built into the cliffs. Others operate hotels and guesthouses that allow visitors to experience the feeling of sleeping inside ancient stone walls.

Tourism has made Cappadocia one of Turkey’s most visited regions. Hot-air balloons rise over the valleys at dawn, floating above the same formations where the cave dwellers once worked and farmed. Yet despite modern growth, the underground world remains carefully protected. Archaeologists continue to uncover new tunnels, suggesting that many more cities lie hidden beneath the surface.

The story of Cappadocia’s cave-dwelling communities is therefore not frozen in the past. It continues in daily life, in restored homes, and in the deep respect that residents hold for their ancestors’ skill and endurance.

The Lasting Legacy of a Subterranean Civilization

The underground world of Cappadocia stands as an example of human adaptability. Generations turned stone into shelter, transformed danger into opportunity, and created a network of communities that thrived beneath the earth.

Their story demonstrates how engineering, culture, and necessity can shape a unique way of life. It offers lessons on resilience, cooperation, and respect for the environment. While the cave dwellers no longer live entirely underground, the history they left behind continues to spark curiosity and admiration around the world.