This is the touching story of a 5-year-old girl named Lina Medina and how she gave birth at the age of five. It all began in the spring of 1939 at a small Andean village in Peru that left one of the most unusual medical records in history.

The beginning

Lina was born in Ticrapo, a mountain community in the Huancavelica region of Peru. Her family lived a modest life shaped by traditional work routines common to the Andes at the time. Nothing about her early years drew attention. She played with other children, followed household routines, and lived beyond the reach of newspapers or global observers. It was a world of quiet roads, adobe houses and long walks between settlements.

This changed when Lina’s abdomen began to enlarge. Her parents assumed she was suffering from a stomach condition. Illness was familiar enough in the region, and travel to a city hospital was often a last resort. But when home remedies brought no improvement, her father took her to doctors in nearby towns, and later to a hospital in Lima. What happened next was recorded by physicians who did not believe what they were seeing until additional examinations confirmed it.

A diagnosis that defied expectation

At the hospital, doctors examined Lina and concluded she was in the late stages of pregnancy. The medical team refused the possibility at first, since Lina was only five years and seven months old. After multiple evaluations, including X-rays and other examinations available at the time, the conclusion remained unchanged. She was pregnant.

The case drew immediate attention among medical professionals. Newspapers soon heard of it as well, but the most reliable material about the case comes from medical journal reports prepared by Dr Gerardo Lozada, the physician who oversaw her care, and later summaries published in reputable medical periodicals.

The pregnancy was the result of a condition known as precocious puberty, a rare disorder in which a child’s body begins maturing far earlier than normal. In Lina’s case, the maturation occurred at a pace extreme enough to make pregnancy biologically possible. Doctors reported that she had developed reproductive features typically seen in adolescents, though no explanation was offered for why her body matured so rapidly. No modern biological test existed at the time that could provide clear answers. As a result, her case remains rare, medically documented, and still cited in pediatrics as the earliest confirmed case of human pregnancy.

The birth

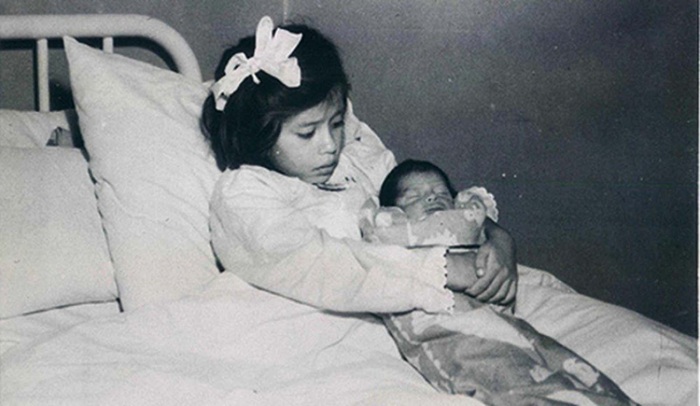

On May 14, 1939, Lina gave birth to a healthy baby boy through a Caesarean section. The procedure was considered necessary because her small pelvis made natural delivery impossible. The baby weighed approximately six pounds, a typical newborn weight, and was named Gerardo after Dr Lozada.

Medical teams continued to monitor Lina and her son after the birth. Reports describe her as calm, and contemporary accounts note that she cared for the infant as any mother would, despite her young age. The child was raised as a sibling within the household for several years before learning the truth about his parentage.

Gerardo lived a normal life and died in his early forties due to an unrelated illness. Lina later married and had another child as an adult.

A case examined by science, not speculation

Because the case involved a child, ethical concerns guided how information was handled from the beginning. The hospital protected her identity, and only limited details were released for medical documentation. Photographs created at the time were reviewed by medical boards before publication. Modern medical historians continue to treat the case cautiously for this reason.

The scientific focus remained on Lina’s condition of precocious puberty rather than on the pregnancy itself. Doctors who evaluated her noted that she had begun menstruating at an extremely early age, although the exact timeline varies among published accounts. Some reports suggest this began at eight months old, others at two or three years, though the wide range reflects uncertainty rather than contradiction. Medical record-keeping in rural Peru in the 1930s was inconsistent, and much information was gathered through interviews with family members rather than written records.

The key medical point is that Lina displayed signs of early maturation long before most other children, which made the pregnancy biologically possible even though it was extremely rare.

One subject that often appears in popular accounts concerns the identity of the baby’s father. The case occurred during a period when forensic science and child-protection laws were far less developed. Authorities conducted an investigation, and her father was detained briefly, but officials released him due to lack of evidence. No one was ever charged. Lina never spoke publicly about the circumstances, and medical teams maintained patient confidentiality. Because reliable testimony does not exist, modern researchers do not offer explanations. It remains the one part of the story that cannot be answered responsibly.

Lina and her family stepped back into private life, and her name appeared only occasionally in medical reviews. Those who knew her described her as reserved, protective of her privacy and uninterested in further publicity. Peru’s government and international journalists respected her family’s requests across the decades.

She later worked in the clinic of Dr Lozada, the same physician who oversaw her care. Reports from former colleagues describe her as diligent and soft-spoken. Over time she created a life away from media scrutiny. She married and had another son in adulthood. Her later years were lived quietly in Lima.

Her story, however, continued to circulate in medical schools. It appears in textbooks and peer-reviewed articles as a documented example of extreme precocious puberty. The case also reinforces the importance of early medical evaluation when children present unusual developmental signs.

Understanding Lina’s case requires a sense of what precocious puberty means in medical terms. It refers to the onset of puberty before age eight in girls and before age nine in boys. Causes can include genetic factors, hormonal imbalances, tumors affecting the endocrine system, or unknown influences. In many cases the cause cannot be identified even with today’s technology.

Children with this condition often grow rapidly at first but may stop growing earlier in adolescence, which can limit adult height. Treatment today may involve medication to slow puberty until an age closer to the typical range. None of these options existed during Lina’s childhood.

Her case is extraordinary not only because puberty arrived unusually early but because the physical maturation was advanced enough to allow the body to sustain a pregnancy. Modern science recognizes this as an outlier rather than a pattern.

Across decades, reputable historians and medical professionals have approached the case with restraint. Even today, scholars refer to her respectfully and avoid speculation about unverified aspects of her life. This has made her case a model for how sensitive medical history should be handled.

Despite global attention in the late 1930s and early 1940s, those who met Lina in later years described her as a woman who preferred ordinary routines. Colleagues recalled that she worked quietly at the clinic, helped organize files, and tended to patients in practical ways. She did not speak publicly about her experience, and few who knew her would bring it up.

Her son Gerardo grew up healthy, studied in local schools, and worked in clerical jobs before he died in adulthood. Accounts describe him as kind, sociable and devoted to his family.

For Lina, the most remarkable part of her life may have been her ability to live beyond the event that brought her name into medical literature. Her story reflects strength more than spectacle, and today researchers view her less as a curiosity and more as a reminder of the human capacity to endure.

Medical lectures still cite her case when discussing anomalies of development. Her pregnancy is one of the earliest confirmed in scientific history, and because it was documented through clinical examinations and surgical records, it remains the most famous example of extreme early puberty.

Doctors today use the case to highlight why early evaluation is important when parents observe unusual physical changes in young children. The story also helps modern medical students understand that scientific records must be handled with respect for the individuals involved.

Lina Medina’s story sits at the intersection of medicine, history and ethics. Though the case is unusual, the lessons drawn from it are familiar: respect for patient dignity, caution with sensitive information, and humility in the face of medical mysteries that continue to challenge our understanding of the human body.