This is the story how Russian hacker, Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev turned code into a $100M heist.

On a wet spring morning in 2011, a routine-looking email slipped into an office inbox somewhere in the United States. An employee clicked a link, opened a document, and the machine hummed as a small, invisible agent slid into the operating system. Over months the agent learned the rhythms of that bank’s back office: which terminals approved wire transfers, how tellers routed exception cases, the exact wording of internal memos. It waited. When it moved, the transfers it generated looked like routine business. Funds streamed out in small, plausible batches and then sprinted through a maze of mule accounts, prepaid cards, shell companies and, eventually, cryptocurrency rails. By the time the pattern became visible, the money was already gone.

That is the short version of how the Gameover ZeuS botnet — and the man U.S. authorities accuse of creating it, Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev — helped turn lines of code into more than $100 million in thefts from businesses and consumers around the globe. The story is technical, patient and deeply human: social engineering that preyed on gatekeepers, software that masked itself inside legitimate processes, and an ecosystem of collaborators who moved money out of sight. It is also a story of international policing, a dramatic takedown operation, and a reward poster that hangs on FBI pages to this day.

The coder and his creation

Bogachev, born October 28, 1983, and known online by handles such as “lucky12345” and “slavik,” emerged in criminal malware circles as an author and operator of Zeus-family banking Trojans. His best-known product, Gameover ZeuS (GOZ), combined credential theft with a resilient peer-to-peer command network that made it harder to shut down than older, centralized botnets. Where earlier Zeus variants were sold as kits, GOZ became a managed service: a “business club” that charged access and offered technical support to affiliates who used the malware for targeted bank fraud and credential harvesting. Security research and law enforcement estimates attribute hundreds of thousands of infections to GOZ at its peak and losses totaling roughly $100 million tied to the botnet’s theft campaigns.

The malware’s technical design reflected that ambition. Instead of relying on fixed command servers that could be seized, GOZ used a peer-to-peer topology and domain-generation algorithms to hide its control channels. The toolkit also included modules for keylogging, form-grabbing (stealing credentials entered into browsers), and remote control. Operators could watch an infected workstation, collect credentials, and then use that information to forge transactions that complied with an institution’s normal processes — the cyber equivalent of watching a bank teller’s routine and then imitating it with a criminal’s card. The operation blurred the boundary between technology and tradecraft: code automated the grunt work, while human operators managed cashout and money laundering.

How the thefts worked — a patient, human-centered crime

What made the Gameover ZeuS scheme especially effective was how it combined automated intrusion with human reconnaissance. The infection was just step one. After that came weeks or months of observation. Attackers recorded keystrokes, captured screenshots, and harvested cookies and session tokens. With those artifacts, they could impersonate employees, access internal dashboards, and craft fraudulent transfers that fit existing patterns. Small-dollar transfers over many accounts, or subtle ledger adjustments, were less likely to trigger alarms than an immediate large withdrawal. Then the cashout network took over: mule accounts received the funds, transshipped them to other jurisdictions, and funneled the proceeds into crypto or prepaid instruments. Each link in that chain increased the distance between the stolen funds and the operator.

The victims were varied. Small businesses, community banks, and individual account holders discovered unauthorized withdrawals and drained balances. Some companies never fully recovered lost records or money. For security teams, the forensic trail was messy: attackers disabled logs, used anonymizing infrastructure, and relied on the international dispersion of mule networks to complicate asset freezes. For investigators, the path forward required piecing together server records, money-movement data, and intelligence from private-sector partners.

The international response: Operation Tovar and the takedown

By 2014 the scale of Gameover ZeuS and associated ransomware (notably CryptoLocker) forced a coordinated response. The U.S. Department of Justice, the FBI, Europol and partner agencies worked with numerous private cybersecurity firms to execute a multinational operation aimed at disrupting the botnet’s infrastructure and rescuing victims. The operation — widely reported under names like “Operation Tovar” — involved sinkholing command channels, seizing or redirecting domains, and building a forensic picture from captured data. For a time the effort succeeded in cutting off significant portions of GOZ’s command network and in recovering data that helped decrypt files locked by CryptoLocker.

The takedown was not a single cinematic raid but a carefully choreographed sequence: private firms detected command patterns and reverse-engineered the botnet’s domain-generation algorithm; law enforcement prepared legal tools and coordinated domain redirection; and multiple countries moved to seize servers or block communications that would otherwise have restored the botnet. The immediate result was a disruption of GOZ and a dramatic slowing of CryptoLocker activity. Yet in the long game, malware authors adapt: variants later reappeared, operators shifted to new toolsets, and affiliates learned to obscure their cashout channels better.

Indictments, arrest warrant and the $3 million reward

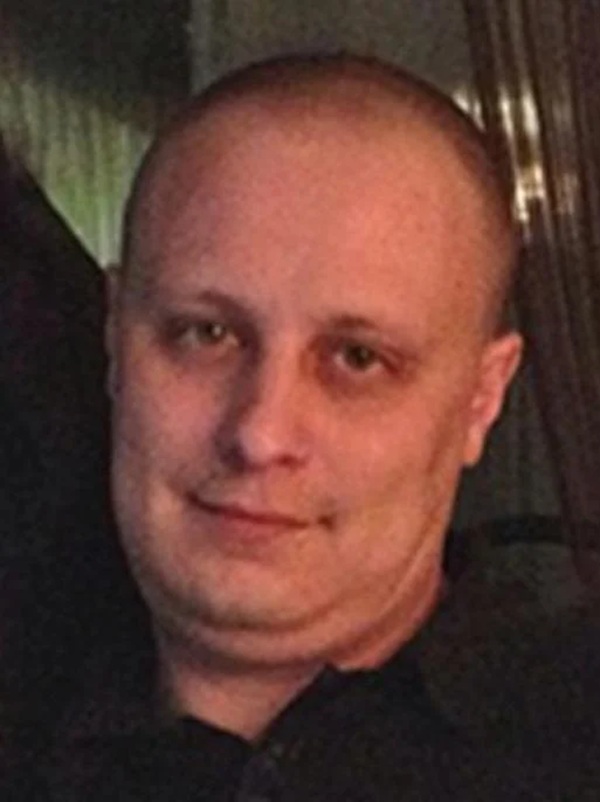

The legal response focused both on disruption and on accountability. U.S. prosecutors unsealed charges against alleged administrators of Gameover ZeuS, including criminal complaints and indictments that named Bogachev by real name and aliases. The Department of Justice and the FBI publicly attributed the botnet’s development and administration to Bogachev and a close circle of associates. In February 2015, with the case still open, U.S. authorities announced a reward of up to $3 million for information leading to his arrest or conviction — at the time one of the largest bounties ever offered in a cybercrime investigation. The FBI also placed Bogachev on its Cyber’s Most Wanted list and published a wanted poster that included photos and identifying details. Today, unsealed court documents outline charges including conspiracy to commit bank fraud, wire fraud, computer intrusion and money laundering tied to the Gameover ZeuS operation.

That $3 million reward signal reflected two truths. First, the scale and cross-border harm of the operation justified an aggressive response. Second, holding suspects to account in cyber cases often depends on tips and international cooperation; offering a reward is one of the practical levers available when suspects remain in jurisdictions that do not readily extradite. Bogachev was believed to be in Russia; the United States has no extradition treaty that would make quick transfers from Russia routine, which has complicated efforts to bring him before U.S. courts.

The evidence trail: how investigators connected Bogachev to GOZ

At the heart of the prosecution’s case is a familiar forensic trail: IP addresses, email usage, server logs, malware signatures, and human sources. Investigators used a combination of technical indicators from sinkholed infrastructure, intelligence from hosting providers, and tips from sources with knowledge of the operation. One noteworthy piece of tradecraft: analysts matched an IP address used to administer part of the botnet to an IP used to access an email account that contained Bogachev’s handle. Despite attempts to anonymize activities with VPNs or intermediaries, small errors — the reuse of the same anonymizing account for different purposes, for instance — provided the cross-links that investigators needed. Private security firms, particularly those that had been tracking Zeus variants for years, also contributed analysis that tied distinct campaigns back to the same code base and operator signatures.

Court filings and public DOJ materials released during the 2014–2017 period summarize these links and the investigative steps used to attribute the malware to Bogachev. Those documents also include technical exhibits, sample malware code, and the procedural history of the takedown. While no single piece of evidence carries the case alone, the combined record supported charges and the public naming of the suspect.

Where is Bogachev now? Current status and public assessments

Publicly available information since the indictments indicates that Bogachev remains at large. U.S. law enforcement has said he is believed to be in Russia. Russia has historically been reluctant to extradite nationals accused of crimes abroad, and there have been no public reports of Bogachev’s arrest by Russian authorities. The FBI’s wanted page and the U.S. State Department’s Transnational Organized Crime Rewards program maintain the reward offer as an incentive for information leading to capture. Journalistic accounts and cybersecurity reporting have speculated about his movements — sometimes placing him in Krasnodar or along the Black Sea — but these reports rely on intelligence that law enforcement does not always publicly confirm.

It is worth noting that being at large is not the same as being operational. The takedown of Gameover Zeus and the sustained pressure from law enforcement and sanctions have disrupted the particular infrastructure Bogachev once managed. However, research and enforcement experience show that authors and affiliates evolve their tools, sell or lease access, and migrate to new criminal enterprises. The cybercrime landscape is adaptive; a successful takedown reduces risk for a time, but does not permanently remove the incentives that produced the crime.

The human cost and the institutional lesson

If the headlines dwell on millions and indictments, the real victims are often small businesses and ordinary people who lost account balances, had to rebuild credit, or suffered disrupted operations. For banks and financial institutions, the Gameover ZeuS saga reinforced a familiar lesson: technology alone is not enough. Attackers exploited human trust and process gaps as much as software vulnerabilities. The defenses that matter are layered: hardened endpoints, strict privilege controls, behavioral monitoring for anomalous approvals, multi-person authorization for critical transfers, and continual staff education on social engineering. Public-private information sharing and rapid cross-border law enforcement collaboration also matter because the cashout network spans jurisdictions.

Operation Tovar and the subsequent legal actions represented a milestone. They showed that international coalitions, working with private security firms, could disrupt complex botnets and rescue at least some victims. The operation also pushed security vendors and institutions to invest more in incident response, threat intelligence sharing, and botnet tracking. Yet the underlying incentives remain: as long as money flows through digital rails and human authorizers exist, there will be miscreants ready to exploit them.

Perhaps the more practical change is cultural. Banks now more often assume breach scenarios, design for compartmentalization, and require stronger out-of-band verification for unusual transfers. Lawmakers and regulators in some jurisdictions have also taken notice, pushing for better reporting obligations around breaches and faster coordination across borders. But full containment of transnational cybercrime would require sustained, synchronized effort across many countries — a high bar.

The Gameover ZeuS story is a study in how software becomes a weapon when married to human cunning and organized laundering. Evgeniy Bogachev stands accused of building and administering one of the most effective banking Trojans of its era. The indictments, the takedown, and the $3 million reward form a public ledger of the legal and operational pushback. But the broader message is enduring: defenders must combine technical rigor with process controls and international cooperation, because the primary vulnerability in many systems remains human trust.