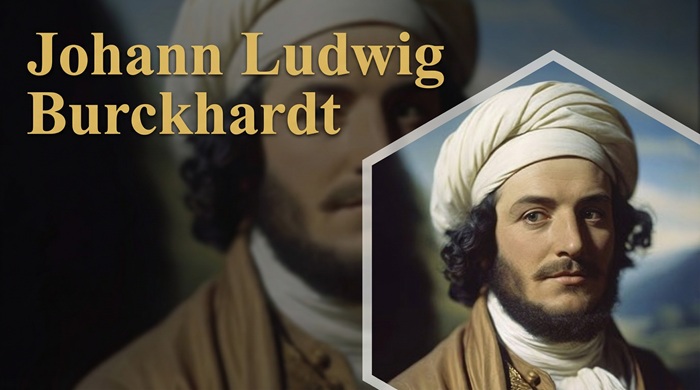

Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, the man who found a lost city was a careful reader of maps, a student of languages, and a restless curiosity who preferred the company of books and camel drivers to comfortable salons. Yet on a late summer day in 1812, dressed as a Muslim pilgrim and carrying the modest confidence of a traveller who had learned the rules of another world, he stepped through a narrow cleft in a rocky ridge and found a city carved in stone — an ancient capital whose scale quieted even the loudest imagination. Europeans called it the “lost city”; the people who had long known its existence called it Wadi Musa. He would later write that the place had “a character which no language can convey” — and in that strip of rock he changed how the world would remember the Nabataeans.

This is not the tale of a lucky stumble. It is the account of a mind that prepared for discovery by learning to listen: learning Arabic, dressing as a local, practising the rites of hospitality and small talk that make strangers welcome. It is the story of how scholarship and patience, when married to courage, open doors that armies and merchants cannot. Below is the long arc of Burckhardt’s life — his quiet training in Europe, the years of disguise in Syria, the day he asked to sacrifice a goat at a tomb and was led to Petra, and the work that followed as he recorded what he saw and told the modern world a city had returned to daylight.

Lausanne to London: A Scholar Sets Out

Johann Ludwig Burckhardt was born in Lausanne on 24 November 1784 into a Swiss family that valued learning. He trained as a language scholar and orientalist at a time when Europe’s interest in the Near East was growing. The British-backed African Association — an organization devoted to exploring Africa’s interior and its trading routes — employed young men able to pass in the regions they visited. Burckhardt answered the call. He learned Arabic, studied Islamic customs, and prepared to leave familiar Europe behind. His teacher in London, Silvestre de Sacy and others in the circle of Oriental studies, taught him not only grammar and vocabulary but the subtle habits that would convince a stranger that he belonged.

What mattered most for Burckhardt was not conquest but concealment. He knew that a European man in certain parts of the Ottoman domains could be assumed to be a “treasure seeker” or a spy — and that assumption might be dangerous. So he adopted a name and a persona: Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah. He grew a beard; he practised the prayers and vows of a Muslim traveller; he learned to keep his eyes lowered at proper times and to accept hospitality with humility. In short, he practiced the art of “passing” as a local, not for vanity but for survival and research. Those skills would allow him to travel in regions closed to Europeans and to record details other travellers could not.

In Aleppo and the Roads of Syria: Patient Work in Plain Sight

Burckhardt arrived in Aleppo in 1809 and spent two years mastering local speech and building trust. He did not rush toward ruins or follow the easy tracks of European curiosity. Instead he travelled as an impoverished Arab would: sleeping by caravanserais, eating simple food, listening to traders and Bedouin guides. He made careful notes about customs, routes, vocabulary, and place names. This patient apprenticeship in living the region’s rhythms explains why — when he finally arrived at Petra — he could move undetected among the local guides who had guarded their knowledge for generations.

Writing later about these years, Burckhardt recorded customs and proverbs with the temper of a field scholar. Travel, for him, was ethnography as much as exploration. His notebooks from Syria show more care for the day-to-day life of the people he met than for the spectacular alone. He learned that to be accepted by Bedouin guides you first learn to be respectfully unremarkable. That modesty would provide him the most remarkable view of all: an ancient city whose façades were carved from rose-coloured stone.

The Ruse of the Goat: How a Sacrifice Led to a City

On 22 August 1812, while making his way from Damascus toward Cairo, Burckhardt heard rumours of ruins in a narrow valley near the supposed tomb of Aaron (Haroun), traditionally located on a high ridge above the area. The tales had been whispered among travellers for some time; earlier Europeans had heard them but approached with caution. Burckhardt needed a credible reason to visit the site without arousing the suspicion of Bedouin guardians who distrusted Europeans. His solution was small, practical, and culturally plausible: he told a local guide that he had vowed to sacrifice a goat at Aaron’s tomb. This request, ordinary within a local religious frame, furnished him with the pretext to be led into the rocky gorge that opens on Petra.

He later described the moment with the economy of a scholar and the wonder of a poet. After stepping into the narrow Siq — the gorge that guides the eye and the caravan into the city — he found himself facing monumental façades cut in warm stone. The scale was astonishing: tombs and temples, elaborate façades carved into the living rock, an urban plan that testified to centuries of commerce and engineering. Yet Burckhardt lingered only briefly. He feared being exposed as an infidel searching for treasures and was careful to make his visit appear pious rather than archaeological. He drew quick notes and left that same night, carrying a handful of sketches and a list of local names, to avoid lingering among suspicious men.

That modest ruse — the vow to sacrifice a goat — is as memorable as the discovery itself because it reveals how small acts of cultural fluency can unlock the largest of places. Burckhardt did not blast a doorway into antiquity. He asked, in a way that made sense to his company, for permission to enter. The permission that followed allowed him to witness a city that European maps had for centuries mostly noted as a ruin in legend.

What He Saw and What He Wrote: Careful Notes from a Brief Visit

Because Burckhardt feared that staying too long would expose him, his first report on Petra was necessarily cautious. Years later, after his death, his travellers’ accounts were gathered and published by the African Association and others; those publications contained the first clear European descriptions of Petra’s carved façades, tombs, and water systems. Burckhardt wrote in measured, plain language, describing the monumental Treasury (Al-Khazneh), the obelisks, the colonnaded streets, and the complex Nabataean hydraulic works that allowed the city to thrive in a dry region. For the modern reader his prose is almost clinical in its restraint; it gives space to the architecture rather than the man.

His notes mattered not only because they reported a spectacle. They mattered because they recorded place names, Bedouin accounts, and routines. Those details allowed later travellers and scholars to interpret Petra as a living centre of Nabataean trade and administration, rather than merely as a romantic ruin. Burckhardt’s recordings laid the groundwork for archaeology that would follow in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Beyond Petra: Abu Simbel and Nubia

Petra was not the only major site Burckhardt encountered. On his later journeys he travelled into Nubia and reported on the rock temples of Abu Simbel — monumental works later associated with the pharaoh Ramesses II — which had been long known locally but were little described in European sources. His willingness to travel far, learn local knowledge, and record what he saw made him a conduit between two worlds: the oral memories of desert peoples and the literate archives of Europe.

His pattern of travel — careful preparation, disguised passage, then swift recording — was shaped by the realities of the age. The Ottoman provinces he crossed were not uniformly peaceful. Banditry, local rivalries, and mistrust of outsiders could make even a simple visit dangerous. That Burckhardt survived these journeys and returned with coherent notes speaks to his combination of cultural skill, patience, and luck.

Publication, Reputation, and the Posthumous Record

Burckhardt died young, in Cairo in 1817, before he could fully publish all his notes. Friends and colleagues at the African Association edited and published his accounts posthumously: Travels in Nubia (1819), Travels in Syria and the Holy Land (1822) and Travels in Arabia (1829) among them. Those volumes brought his observations to a wide European audience and established his reputation as a precise and observant traveller. His method — living as closely as possible to the people he studied and writing soberly about what he found — influenced later generations of explorers and scholars.

His work also raised questions about ownership and representation. The nineteenth-century pattern of European travellers “rediscovering” sites already long known to regional peoples has been criticized for erasing local continuities of knowledge and authority. Burckhardt’s notes, to his credit, often acknowledged the local guides and Bedouin who knew much of the terrain and the place-names. Still, the fame attached to his name shows how European publication can overshadow the lived knowledge of local communities — a dynamic scholars now examine with care.

The Man Beyond the Discovery

What type of man does one need to be to accept a life of travelling for the sake of knowledge? Burckhardt’s temperament was a mixture of scholar, mimic, and practical adventurer. He wrote lists of proverbs and patiently recorded the customs of markets; he also knew how to bargain for a camel and how to feed both camel and guide. He appears in his notes as modest and precise, more interested in compiling truthful accounts than in Romantic embellishment. That attitude made his accounts useful to both scientists and future travellers.

He was not untouched by the era’s prejudices. Like many European Orientalists of his time, he wrote in terms shaped by a colonial age and carried assumptions about difference. But he also modelled a form of travel that prioritised listening — an approach that modern fieldworkers continue to value. In his careful descriptions of Bedouin customs, place names, and local topography, he preserved a wealth of ethnographic detail that might otherwise have been lost.

Petra’s Afterlife: Tourism, Archaeology, and Memory

The rediscovery of Petra by European letters helped shape its later afterlife. As the site became known, explorers and archaeologists returned, documented monuments in more detail, and began preservation work that continues today. Petra became a symbol — of ancient trade networks, of Nabataean skill, and increasingly of Jordanian national heritage. Modern Petra, protected and managed, receives hundreds of thousands of visitors each year, its stone façades staged now between the Siq and a bustling visitor economy. The story of Burckhardt’s single day there sits beside the longer human story of the Nabataeans and the Bedouins who kept knowledge of the site alive across centuries.

When tourists stand before Al-Khazneh and imagine the moment the gorge opened onto a city, they touch a concentrated history: of ancient trade routes, of European curiosity and scholarship, and of the local custodians whose names seldom make it into printed travelogues. That layered history is what scholars now call “heritage” — a story made by many hands, not only by the first European to publish an account. Burckhardt’s role is significant; it is not the whole story.

What the Goat Tells Us About Exploration

There is an appealing compactness to the anecdote: a single goat, a short prayer, and a man is shown a city. The simplicity of the moment hides the long apprenticeship that made it possible. Burckhardt’s goat was an instrument of plausibility: a culturally credible excuse that allowed him to pass where others might be refused. It shows how exploration is often as much about listening and plausible pretexts as it is about maps and courage.

For modern readers the lesson is both practical and ethical. The practical lesson is straightforward: careful learning of local language and custom opens doors. The ethical lesson is more complex: the story forces us to consider who gets credit for discovery and how the act of “rediscovery” can both reveal and obscure the lives of the people who maintained knowledge across generations. Burckhardt’s modesty in his accounts — his reluctance to linger, his respect for local knowledge — complicates the standard portrait of a European hero and invites us to read his notebooks not as imperial trophies but as documents of ethnographic exchange.

Johann Ludwig Burckhardt died in Cairo in 1817, aged thirty-two. He had widened the map of European knowledge of the Near East in ways that endured: Petra entered scholarly literature, Abu Simbel and Nubia appeared on more accurate itineraries, and his ethnographic notes supplied later researchers with place-names and customs that might otherwise have been lost. His careful approach — blending language study with lived disguise — became a model for travellers and scholars who followed. Yet his life also invites reflection on the ethics of knowledge production: how local knowledges are recorded, who keeps them, and who receives the fame for documenting them.