Most people move through the world with the comfort of memory at their side. They recall familiar faces, hold on to moments that shaped them, and build a sense of self from a long chain of recollections. Memory offers continuity. It tells a person who they were yesterday and who they hope to become tomorrow.

For one man, that chain broke in an instant. His name was Henry Molaison, though the world came to know him simply as HM. His life changed after a medical decision meant to save him from constant seizures. The procedure relieved his suffering but left him unable to form any new memories. What he experienced each day felt as if time had been cut into a series of short pieces. Every half minute, the world seemed new again.

His story became one of the most important in modern neuroscience. It revealed what memory is, how fragile it can be, and how deeply it shapes identity. It also remains a human story, marked by quiet courage and a life lived in the present because the past could no longer grow.

A Childhood Marked by Uncertainty

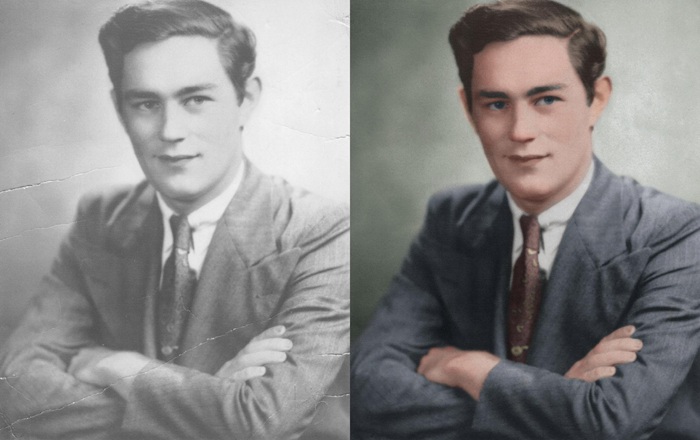

Henry was born in 1926 in Connecticut. He grew up in a modest home with parents who worked hard and hoped to give him a stable life. His childhood was ordinary in many ways, but signs of a deeper struggle appeared early. By the time he was a boy, he began having seizures. At first they were manageable, though frightening. As he aged, they grew worse.

During adolescence, the seizures intensified until they disrupted nearly every part of his life. They affected his schoolwork and weakened his confidence. They kept him from forming friendships because he never knew when the next episode would strike. The condition placed a weight on his family as they searched for answers that medical science at the time struggled to provide.

By his twenties, the seizures had become debilitating. He could not work reliably. He could not remain independent. The episodes came without warning, leaving him confused and exhausted. His doctors tried various treatments, but nothing offered lasting relief.

A Risk That Promised Hope

In the early 1950s, brain surgery was still a developing field, yet some specialists believed that removing parts of the brain could reduce seizures. A neurosurgeon named Dr William Beecher Scoville proposed an operation that targeted the areas believed to trigger Henry’s epilepsy.

The procedure was experimental. The risks were significant. Yet for Henry and his family, each day had become a struggle. The hope of a life without constant seizures seemed worth the danger. In 1953, when Henry was 27, he consented to the surgery.

Doctors removed portions of his medial temporal lobes, including a structure called the hippocampus. At the time, the full role of the hippocampus in memory was not well understood. No one predicted how much its removal would change Henry’s life.

A Life Split in Two

When the surgery ended, the seizures improved. They became less severe and less frequent. The operation did, in one sense, achieve its goal. Yet something else had changed, something no one expected.

Henry could no longer create new memories.

He remembered his childhood. He remembered his parents and the house where he grew up. He remembered the years before the operation. But anything that happened after the surgery slipped away moments after it entered his mind.

If someone left the room and returned a few minutes later, he greeted them as though he had not seen them for years. If he ate a meal, he often forgot he had eaten and wondered when dinner would be served. If he answered a question, he sometimes asked why he had been interrupted even though the conversation was continuing from his own words.

His memory lasted only a short span, usually half a minute. After that, each moment felt like a fresh beginning.

Living Inside a Narrow Window of Time

Henry’s days took on a surreal shape. He was aware that something had changed. He understood that he had difficulty remembering. What he missed was the feeling of continuity that others take for granted.

He lived in a perpetual present. He could hold a thought for seconds, then watch it slip away before he could attach it to anything else. To those who met him, he appeared calm and polite. He spoke clearly and understood everything said to him. His intelligence remained intact. What vanished was the ability to add new experiences to the story of his life.

With each passing minute, the world renewed itself. The people around him felt familiar in a distant way, like faces from a dream. The hospital staff often reintroduced themselves, though they had already spoken to him moments earlier.

Many described him as gentle and patient. He did not show frustration except in the rare instances when he was reminded of how much he had lost. Even then, he tried to continue with dignity.

The Scientists Who Learned From His Life

Henry became one of the most studied individuals in medical history. After the surgery, researchers recognized that his condition offered a rare chance to understand memory. Before then, no one knew exactly how memories formed or where they were stored. His case provided answers.

A researcher named Dr Brenda Milner began working with him soon after the operation. She discovered that although Henry could not form new memories, he could learn certain tasks through repetition. He could improve at drawing, tracing, and other skills even though he had no recollection of practicing.

This revealed something essential. Memory was not one single system. It had layers. The hippocampus created new memories of events and facts, but procedural memories such as skills depended on different parts of the brain. Henry taught the scientific community that memory is not a single thread but a woven structure.

His life transformed neuroscience. Researchers from around the world visited him over the decades. They tested his recall, asked about his past, and watched how he interacted with the world. Each observation helped reveal how memory shapes human identity.

The Emotional Weight of Forgetting

While the scientific value of his condition was immense, the personal cost was quiet and profound. Henry lived with his parents for many years after the surgery. He could not live independently, though he managed daily tasks with guidance.

He remained friendly and cooperative. Visitors described him as warm and thoughtful. Yet his relationships lacked the steady growth that memory provides. He met the same people repeatedly without the comfort of familiarity. Friendships depended on others remembering him, because he could not remember them in return.

Though he could not form new memories, he retained his polite nature. He asked gentle questions. He expressed gratitude. In this way, his personality survived even when his ability to record new experiences disappeared.

What His Condition Revealed About Identity

Henry’s story raised questions about the nature of self. If memory creates identity, who is a person when memory is limited to the distant past? Does the self remain stable, or does it drift like a boat whose anchor has been lifted?

For Henry, the answer appeared in his consistent behavior. Despite forgetting new events, he maintained his sense of kindness and calm. He recognized that he was himself. He understood his past, even if he could not build a future in the way others do.

His identity remained, though it lived within a narrow window. He carried himself with dignity despite the fragility of his internal world.

The World Through His Eyes

To understand how he experienced life, imagine waking up and discovering that you cannot recall what happened a minute ago. Books would have no storyline. Conversations would reset before they reached their point. A walk through a neighborhood would feel unfamiliar each time.

Yet Henry handled these moments with remarkable steadiness. When he learned that he had a memory problem, he accepted it. When doctors explained that the surgery changed his brain, he listened quietly, even though he forgot the explanation soon after.

In a journal he attempted to keep, he wrote one sentence again and again: “I am not yet fully awake.” To him, the world always felt like the first moments after opening one’s eyes in the morning, when nothing is fully clear and time seems suspended.

A Life That Shaped Modern Science

Henry’s willingness to participate in years of research changed the world’s understanding of the brain. His case revealed the role of the hippocampus, guided treatments for memory disorders, and helped shape theories about learning, trauma, and aging.

Even after his death in 2008, his contribution continued. His brain was preserved and carefully studied. Researchers mapped it in remarkable detail, providing new insight into the architecture of memory.

His legacy is not the condition he endured, but the knowledge that grew from his courage and patience.

A Gentle Story Behind the Research

Though many think of him as a scientific case, the man himself lived a full emotional life in the ways he could. He enjoyed simple routines. He worked small tasks at a rehabilitation center. He greeted people with interest each time he saw them. He possessed a quiet good nature that left an impression on everyone who met him.

His story is not one of tragedy alone. It is a story of resilience. He lived within a narrow boundary of time but found calm and steadiness inside it. He adapted to a world that renewed itself endlessly.

His contribution to science was immense, yet his humanity was even greater.

The man who forgot his life every 30 seconds changed the understanding of memory more than any discovery in the previous century. His story shows how delicate the brain can be and how deeply memory shapes human experience.

Though he lived with a rare and challenging condition, he remained kind, patient, and steady. His willingness to participate in decades of research paved the way for breakthroughs that continue to guide medicine today.

His life reminds us that identity is both fragile and strong. It exists not only in memory but also in character, kindness, and the way a person moves through the world, even when the past slips quietly away.