The southern highlands of Ethiopia hold many stories that reveal how deeply human history is woven into the landscape. Among the mountains, forests, and scattered farmlands that mark the northern edges of Mago National Park, there is a community whose traditions, language, and way of life have shaped the region for centuries. These are the Ari people, also written as the Aari. Their culture is known throughout the Omo Valley and across Ethiopia for its diversity, craftsmanship, and resilience. In recent years, they have attracted attention from abroad because a small number of Ari individuals naturally possess striking blue eyes, a feature seldom associated with African populations. Yet the Ari story reaches far beyond this single detail. It stretches across generations and reveals a society that has carried its customs, adapted to change, and maintained its distinct identity through time.

To understand the Ari, it is necessary to explore their history, examine their daily life, and consider the environment that has shaped their community. These aspects offer a more complete picture than the surface descriptions that often appear in hurried accounts. Their story is one of continuity, adaptation, and a quiet strength that has allowed them to remain rooted in a fast-changing world.

Geographical Setting and Early Origins

The Ari occupy one of the largest territories in the Omo Valley. Their land extends from the lower slopes of the highlands around Jinka, across fertile valleys, and toward the boundaries of Mago National Park. The region is known for its rich volcanic soil, moderate climate, and dense vegetation. These natural features have shaped the Ari way of life for centuries. While many neighboring groups live in drier environments where pastoralism dominates, the Ari rely heavily on farming. Their land provides a wide range of crops that support both subsistence living and local trade.

Historians and anthropologists often describe the Ari as one of the oldest communities in this part of Ethiopia. Their presence predates the rise of several well-known groups in the Omo Valley. There are long-standing oral accounts suggesting that the Ari may have given rise to other tribes through migration, intermarriage, and the natural movement of people across the region. Whether this is historically exact or not, it highlights the position of the Ari as one of the foundational groups in the wider cultural landscape of southern Ethiopia.

During the late nineteenth century, the expansion of the Ethiopian Empire brought the Ari under imperial rule. Before this period, they lived in independent groups, each led by its own elders and spiritual authorities. The arrival of centralized administration changed aspects of local governance, yet the Ari retained many internal traditions and modes of community leadership.

Agriculture and Economic Life

Agriculture is the foundation of Ari livelihood. The community produces a wide variety of crops across different elevations. Grain, maize, barley, sorghum, coffee, mango, banana, and several root vegetables are grown in large quantities. The high fertility of the soil means that families can cultivate enough food for their own use and still have surplus to sell in markets around Jinka and smaller trading towns.

The Ari have also developed specialized crafts that hold economic and cultural significance. Pottery is one of the best-known traditions. The clay collected from riverbanks is shaped, smoothed, painted, and fired to create cooking pots, water jars, and decorative designs. These items reflect detailed patterns that often carry cultural messages or symbolic meanings. In many parts of Ethiopia, Ari pottery is used daily, which has helped preserve the craft across generations.

Blacksmithing is another valued profession among the Ari. Skilled artisans create tools that support farming, hunting, and household work. Agricultural implements, blades, ornaments, and ceremonial objects are produced in workshops that rely on techniques passed down within families. Blacksmiths hold a respected position in society, since their work supports the entire community.

In recent years, the Ari have expanded their economic activities to include the production of local alcoholic beverages made from fermented grains. This drink is strong and commonly used during cultural festivals, weddings, and gatherings. It is also exchanged in trade, allowing families to supplement their income.

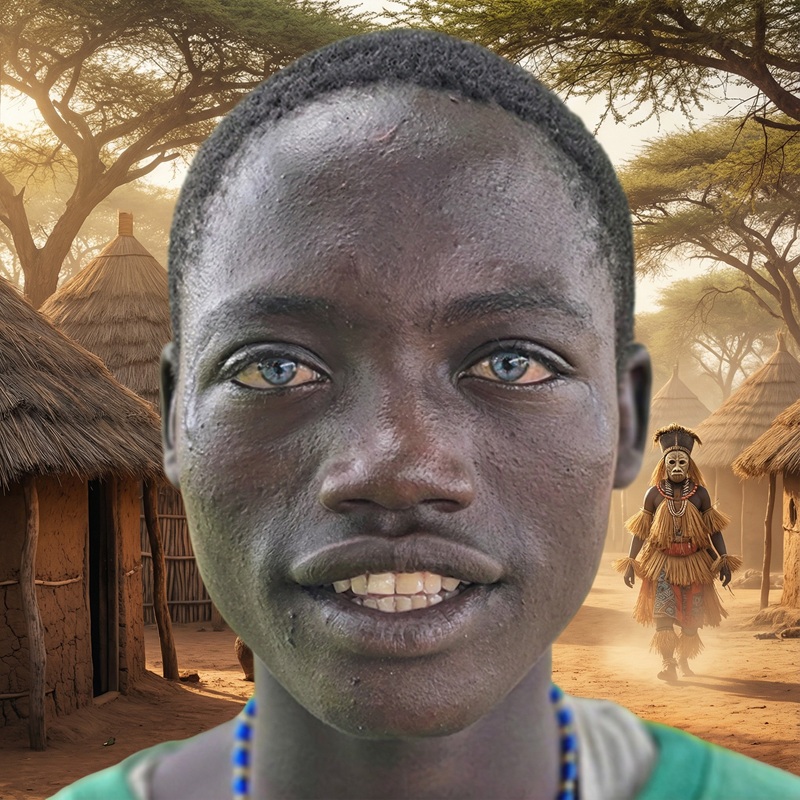

The Blue-Eyed Individuals of the Ari Community

Although most Ari people share the deep brown eyes common across much of Africa, a small number possess natural blue eyes. This physical trait has drawn global curiosity and inspired numerous theories. However, the genetic explanation is far more complex than many assume.

Some observers once believed that blue eyes in Africa must have originated from European ancestry. Trade routes, colonial encounters, or ancient migrations were thought to be possible sources. Yet modern research has shown that genetic mutations affecting eye pigmentation can appear in any population, even in communities that have remained largely isolated.

Scientists point to the OCA2 gene, which plays a central role in melanin production. A mutation in this gene can reduce melanin in the iris, resulting in blue eyes. This mutation can occur naturally, without requiring external influence. Scholars like Professor Hans Eiberg have argued that all humans originally had brown eyes until a change in the OCA2 gene many thousands of years ago produced the first blue-eyed lineage. The mutation then spread through different populations at different times.

There is also a condition known as Waardenburg syndrome. It can alter pigmentation in the eyes, skin, and hair, and may sometimes cause hearing differences. While this condition can lead to blue eyes, it is not widely documented among the Ari, and there is no definitive medical evidence to show that it is responsible for their blue-eyed individuals. As a result, the true cause remains a subject of interest, rather than a settled conclusion.

The presence of blue eyes represents only a tiny part of Ari diversity. Their culture should be understood through a much broader lens that includes language, history, art, and social structure.

Social Structure and Cultural Identity

The Ari community is organized into several territories, each with its own leader. These secular heads manage local concerns, settle disputes, and represent their people in larger gatherings. Alongside them are spiritual leaders known as Babi. These figures offer guidance on matters of tradition, morality, and ceremonial life. Their role was even more central before the spread of Christianity in the region.

Originally, the Ari practiced traditional beliefs rooted in nature, ancestral spirits, and local rituals. Water sources, forests, mountains, and certain animals held sacred meaning. Offerings and ceremonies were carried out to maintain harmony with the environment and the unseen world. Over time, Christian teachings reached the area through missionaries, and the new faith became widespread. This shift influenced family life, marriage practices, and social norms. For example, polygamy, once common, gradually declined as Christian values took hold.

Despite these changes, many cultural practices continue. Women often wear skirts made from plant fibers, especially koisha leaves, and decorate themselves with colorful beads and crafted jewelry. Their homes vary from simple mud-and-wattle structures to bamboo and straw dwellings. Many houses are painted with natural pigments that create geometric patterns and symbolic images. These artistic decorations, known locally as bartsi, are a source of both beauty and cultural identity.

Village life is lively during festivals. Young people decorate themselves with flowers, plant dyes, berries, and ornaments made from animal horns or tusks. Music, drumming, and dance fill the community grounds as families gather to honor shared traditions.

Challenges and Modern Pressures

Like many indigenous communities, the Ari face increasing pressure from modernization. New roads connect previously isolated villages to larger towns. Tourism has expanded across the Omo Valley, bringing both new opportunities and new concerns. Infrastructure projects such as dams and irrigation systems have the potential to reshape the landscape. While these developments promise economic benefits, they also carry the risk of eroding traditional customs and disrupting the environment.

The Ari have responded with resilience. They continue to teach their children the practices of their elders. They still farm ancestral lands, craft pottery, and celebrate cultural festivals. While many young people attend school and seek new forms of employment, they often maintain strong ties to their heritage.

Genetic Diversity and Broader Scientific Findings

Studies on human genetics have revealed that African populations possess the widest genetic diversity in the world. This diversity supports the idea that traits like light eyes or unusual pigmentation can appear without external influence. Research on Melanesians in Oceania, who have both dark skin and naturally blond hair, further illustrates the complexity of human genetics. Their traits are linked to ancient genetic branches that predate modern racial classifications.

In the case of the Ari, this reinforces the understanding that blue eyes should not overshadow the richness of their history. It is only one thread in a much larger story, not the defining feature of their identity.

A Community Preserving its Heritage

The Ari people represent a living example of how a community can remain grounded in its traditions while adapting to a changing world. They continue to farm, craft, celebrate, and guide their children through teachings that have endured for generations. Their culture is shaped not only by their land and history but also by the way they carry forward the values of their ancestors.

Visitors who travel to the highlands near Jinka often remark on the strong sense of pride that exists within the community. The painted houses, the pottery markets, the open fields, and the ceremonial gatherings reveal a society that remains confident in its identity. The Ari story is one of continuity. It is a story of a people who have balanced old ways with new realities. It is a reminder that cultural heritage can survive, even when the world around it changes.