Most people who follow the history of Apple know the names of Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Far fewer recognize the quiet third man who stood beside them at the beginning. His name is Ronald Gerald Wayne. At the dawn of the personal computer era, he held a ten percent share in a company that would later become one of the world’s most powerful corporations. He sold his part for eight hundred dollars. The value of that share today is measured in tens of billions. His story is often summarized in a single sentence, yet the life behind that sentence is richer and far more complex.

Ronald Wayne was born on May 17, 1934, in Cleveland, Ohio. His childhood carried none of the signals one might expect from someone who would later help form a historic company. He grew up in a modest environment during the final years of the Great Depression. Money was tight, and opportunities were limited. What stood out in Wayne was his early interest in understanding how things worked. Machines and devices held his attention, and he enjoyed the quiet satisfaction of solving mechanical problems. He never presented himself as a prodigy. He was simply a boy who liked to take things apart and put them back together.

His education followed the same practical pattern. In 1953, he completed his studies at the School of Industrial Arts in New York. The institution prepared students for the applied fields of engineering, design, and drafting. For Wayne, it opened a path toward a hands-on understanding of technical work. He later taught himself additional skills related to product development and electrical engineering. These abilities became his toolkit in a country moving steadily into a technological age.

In his early twenties, Wayne made a decision that shaped the direction of his working life. He left the East Coast for California, where aerospace and electronics were expanding rapidly. The move placed him in a landscape full of technical companies, new ideas, and the constant search for talent. During his twenties and thirties, he gained a reputation as a reliable draftsman and engineer. Clients and colleagues appreciated the steadiness of his work. He was not a dreamer pushing boundaries. He was the person who made ideas clear, functional, and realistic.

At the age of thirty-seven, Wayne attempted to build something of his own. In 1971, he launched Cyan Engineering. The company focused on the design and development of slot machines. The idea fit his technical background, but the business side proved more difficult. Managing finances, selling products, and competing against larger companies strained the young business. When the company collapsed, Wayne carried the responsibility on his shoulders. He spent the next year paying back every individual who had invested in his venture. It was an act of integrity that left a lasting mark on his thinking. From that moment, he viewed risk through a different lens. He knew the weight of failure. He knew what financial liability could do to a person’s stability, and he learned to distrust ventures that carried high levels of uncertainty.

By the mid-1970s, Wayne was working at Atari as Chief Draftsman. The company was growing rapidly during the early wave of video game popularity. The atmosphere inside Atari was often hectic, but Wayne’s grounded approach earned respect among his colleagues. It was there that he met two young men who would change the course of his life: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.

Jobs was intense, persuasive, and determined. Wozniak was quiet, brilliant, and focused on engineering challenges. Wayne was older than both of them by nearly two decades. Jobs in particular sought him out for guidance. He saw in Wayne someone who understood contracts, technical documentation, and the general structure of a business. The two younger men were full of creative energy, but neither had experience with the formal side of an enterprise. That balance made Wayne valuable.

In 1976, Jobs approached Wayne with an idea. He and Wozniak wanted to form a company to sell the computer boards they were developing. They needed someone who could help resolve disagreements, write contracts, and provide enough maturity to make the business appear credible to clients. Wayne agreed to assist, knowing he would not be involved in day-to-day engineering but could help the company establish a solid foundation.

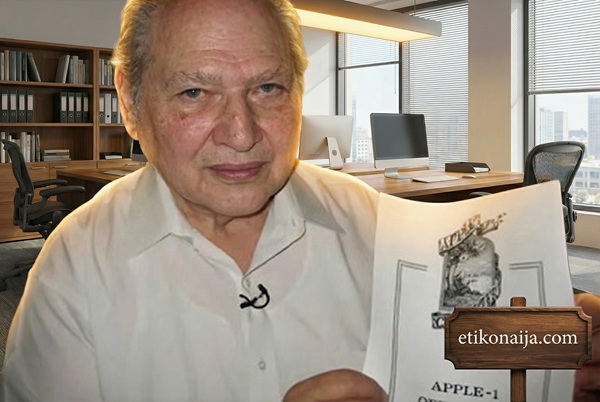

On April 1, 1976, Apple Computer Company was formed. Wayne wrote the partnership agreement. Jobs and Wozniak each held forty-five percent of the company. Wayne received ten percent and the authority to break any deadlock between the two younger founders. In addition to writing the agreement, he produced the first Apple logo and prepared the manual for the Apple I computer. These contributions shaped Apple’s earliest image.

Days after forming the partnership, Jobs secured an order for fifty Apple I computers from The Byte Shop. To fulfill it, he obtained a line of credit for fifteen thousand dollars. This placed the company in debt before it had shipped a single product. For Jobs and Wozniak, risk was part of the adventure. They were young, and they had nothing to lose. For Wayne, the situation was different. Under the laws governing partnerships, all three founders were personally responsible for the company’s debts. Jobs and Wozniak owned very little. Wayne owned property. If Apple failed to deliver the computers or if Byte Shop delayed payment, creditors could pursue him directly.

The memory of his earlier business failure resurfaced. He understood how quickly an optimistic venture could turn into a financial burden. Apple was unproven. Its success was not guaranteed. The personal risk was too great. Twelve days after signing the partnership agreement, Wayne withdrew. He surrendered his ten percent share and received eight hundred dollars in compensation. Later that year, the remaining partners offered him another chance to return. He declined.

In time, Apple grew beyond anything Wayne or the other founders could have imagined. When the company went public in 1980, Jobs and Wozniak became wealthy almost overnight. Wayne’s ten percent share would have been worth billions. As Apple expanded across the world over the next four decades, the theoretical value of that stake rose to levels rarely seen in business history.

Yet Wayne did not express bitterness. He never challenged Apple in court, never argued that he had been treated unfairly, and never demanded recognition. When asked about the decision, he explained that it made practical sense at the time. His caution was not driven by fear or lack of imagination. It was based on experience. He had lived through the consequences of an unsuccessful venture once, and he was not prepared to repeat the outcome. In his own words, he refused to “spend tomorrow grieving over yesterday.”

After leaving Apple, Wayne continued to work in technical fields. He moved through drafting, consulting, and product design. He sold the original partnership document for a modest sum, which would later seem ironic when the same document was auctioned for more than a million dollars. Wayne spent his later years in Nevada, living quietly and speaking occasionally with journalists and historians interested in Apple’s early days. He described himself as content with the life he chose. Wealth did not define success for him. Stability and peace mattered more.

At one point, Jobs invited Wayne to attend a presentation in San Francisco. Apple covered the trip, provided first-class accommodations, and ensured he was treated with respect. The gesture acknowledged Wayne’s role in the company’s beginnings, even though he had left long before Apple reached prominence. The visit reminded him of how different his life would have been had he remained with Jobs and Wozniak, yet it did not alter his sense of clarity about the path he had chosen.

In interviews, Wayne often emphasized that he did not see himself thriving inside a rapidly growing corporation. The environment of a major technology company, with its constant pressure and relentless pace, did not match his personality. He imagined that he would have ended up managing documentation departments rather than shaping new inventions, and that future did not appeal to him. He valued a measured, predictable life, built around personal interests rather than corporate ambition.

Wayne’s story is often portrayed as a misstep. In truth, it is a study in how individuals weigh risk, past experience, and personal values. He made his decision with a full understanding of the potential consequences. His choice reflected a desire for stability rather than a lack of foresight. Many entrepreneurs chase extraordinary success without recognizing the emotional and financial burdens that follow. Wayne recognized those burdens early and chose a quieter life.

He summed up his perspective with a piece of advice that continues to resonate. He encouraged young people to find work they would gladly do without expecting payment. In his view, fulfillment came from meaningful effort, not from the size of a bank account. That philosophy guided him long after Apple became an international giant.

Ronald Wayne’s story holds a certain power because it offers an unusual contrast. In a culture that often celebrates dramatic success and financial triumph, he represents a different form of wisdom. He placed stability above fortune, peace above risk, and personal satisfaction above the pursuit of wealth. His life illustrates that value lies not only in what one gains, but also in what one chooses to avoid.

He remains a part of Apple’s story, not because he stayed, but because he recognized what he wanted from life and acted accordingly. His decision shaped the path of the company, yet it also shaped the path of his own life. In the end, Ronald Wayne stands as a reminder that the measure of a life is not limited to material success. It can also be found in the quiet confidence of a choice made with clarity and purpose.