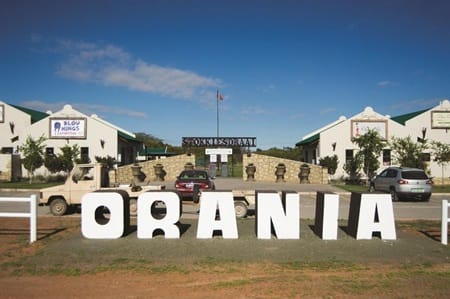

There are many controversies surrounding Orania, a small town in South Africa that’s white-only. In this town in South Africa, Black people are not allowed to live or marry. This self-governing white Afrikaner town was founded in 1991 and is located in the Northern Cape province of South Africa. It caters only to white people and adheres to Afrikaner culture.

Tucked away in the arid expanses of South Africa’s Northern Cape province lies Orania—a seemingly unassuming town that has, over the years, grown into one of the country’s most controversial symbols of separatism. It’s a place where the past is not just remembered but almost reverently preserved. Where apartheid’s ghost has not only lingered but seemingly taken up residence. At the heart of this town of 3,000 lies a towering statue of Hendrik Verwoerd—the very architect of apartheid. And if that’s the first thing you notice when you step into Orania, then you’ve already stepped into a different reality. This is not just another town. It’s a socio-political anomaly, a cultural defiance, and for many, a sharp reminder of a dark, segregated past.

Orania: The White Only Town in South Africa

The idea of Orania wasn’t conceived in haste. It was born from ideology, cultivated in the mind of one man—Carel Boshoff. In 1991, just as apartheid was beginning to loosen its grip on South Africa and Nelson Mandela had been released from prison, Boshoff was heading in the opposite direction. While the country edged toward democracy, he was carving out a different vision—one rooted in cultural preservation and ethno-nationalism.

Boshoff, notably the son-in-law of Hendrik Verwoerd, was not merely nostalgic for the past—he sought to recreate it. Using private funds, he bought 1,167 acres of desolate land near the Orange River. This was once a workers’ village built for laborers constructing a nearby dam, with roughly 150 wooden homes, a recycling plant, and a post office. Where others saw abandonment, Boshoff saw the potential for an Afrikaner utopia.

Born in 1927 in North Pretoria, Boshoff held a doctorate in divinity and served as a missionary in Black townships for the Dutch Reformed Church before becoming a professor. But his shift toward Afrikaner nationalism—along with his deep family ties to apartheid’s mastermind—cemented his place in South Africa’s far-right ideological sphere. Orania, to Boshoff, was not just a town. It was a mission.

Who are the Afrikaners?

To understand Orania’s ethos, one must also grasp the psyche of the people it was designed for. Afrikaners, or Boers, are descendants of Dutch settlers who arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652. Over the centuries, they established a distinct identity, language (Afrikaans), and culture rooted in Calvinism, self-reliance, and—most problematically—a belief in white supremacy.

Under apartheid, Afrikaners became the ruling class. They held political power, controlled land, and implemented policies that subjugated the Black majority. But in 1994, their world unraveled. Apartheid collapsed, the African National Congress rose to power, and Nelson Mandela became president. Many Afrikaners, feeling culturally displaced and politically sidelined, feared assimilation and the erosion of their identity.

A Town With Its Own Rules

Orania is not merely a community; it’s a self-styled mini-state. It has its own currency, called the Ora, its own local government (the Orania Representative Council), and even its own bank. The Ora, introduced in 2004, is pegged 1:1 with the South African Rand but functions more like a local voucher system. While legally it’s not recognized as an independent currency, within Orania, it fuels a localized economy focused on self-reliance.

Agriculture dominates this economy. The town boasts one of the largest pecan nut plantations in South Africa. Dairy farms, vineyards, and pig farming further contribute to its sustainability. There’s no unemployment in Orania—at least not for the white residents. Black labor, however, is conspicuously absent.

And that’s no accident.

The Elephant in the Room: Racial Exclusivity

Orania’s most contentious characteristic is its demographics. The town only allows white Afrikaners to reside there. Black South Africans are not permitted to live, work, or marry into the community. They may visit, yes, but even that is tightly regulated.

It is here that the town’s ideology confronts South Africa’s constitution head-on. The residents defend Orania’s exclusivity by calling it a “cultural project.” They say it’s about preserving Afrikaner identity, not promoting racial superiority. But this claim crumbles under even mild scrutiny.

If Orania is purely about culture, why are non-white Afrikaners excluded? Why is it that in a multi-racial democracy, a town is allowed—tolerated even—to be entirely white?

Critics see through the thin veil. To many South Africans, Orania is a modern-day manifestation of apartheid, camouflaged in legal technicalities and framed as cultural protectionism. It’s not just a town—it’s a provocation.

The Statue That Speaks Volumes

Few things encapsulate Orania’s defiance like the statue of Hendrik Verwoerd. For those unfamiliar, Verwoerd wasn’t just a politician—he was the architect of apartheid. As South Africa’s Prime Minister from 1958 until his assassination in 1966, he institutionalized racial segregation and championed the notion of white superiority with chilling precision.

To many, Verwoerd is a symbol of systemic oppression and generational trauma. To Orania, he’s a founding father.

This reverence isn’t subtle. His bust sits proudly in public view, watched over not with shame but with solemn pride. It sends a clear message: Orania hasn’t just rejected the political shift of 1994—it has actively chosen to commemorate its ideological antithesis.

Legal Loopholes and Semi-Autonomy

So how does Orania exist? How can a town be openly exclusive in a democratic nation with one of the world’s most progressive constitutions?

The answer lies in property law and loopholes. Orania is owned by the Vluytjeskraal Share Block Company. Essentially, it’s private land governed by private agreements. Residents must apply and be approved by a committee, which ensures “cultural compatibility.” In other words: if you’re not a white Afrikaner, you’re not getting in.

While South Africa’s constitution prohibits racial discrimination, it doesn’t override private land ownership rights. This murky legal space allows Orania to operate as a “cultural enclave” rather than an official municipality.

The Orania Representative Council (ORC) handles everything from tax collection to public services. No political parties exist in the town. Officials are nominated, elected, and—interestingly—serve without pay.

In theory, this sounds like direct democracy. In practice, it’s an insulated system designed to perpetuate exclusivity.

Is Orania a racist town?

Orania’s defenders are quick to argue that the town is misunderstood. They point to its low crime rate, clean streets, high employment, and strong community values. They claim it’s a successful model of self-governance and cultural preservation.

But these praises exist within a vacuum—disconnected from the broader national reality. The real issue isn’t whether Orania functions. It’s who it functions for.

No matter how it’s framed, Orania’s foundational principle is exclusion. Its very identity hinges on denying access to those outside the Afrikaner mold. This is not about protecting culture—it’s about controlling space and limiting diversity.

In a country still healing from apartheid’s wounds, Orania is more than a town—it’s a symbol. For many South Africans, especially Black citizens, it’s a slap in the face. A reminder that while laws may change, mindsets can remain stubbornly frozen in time.

The ANC government has occasionally made noise about Orania, but no major legal action has been taken. Perhaps it’s the complexities of property law. Perhaps it’s political calculus. Or perhaps Orania is allowed to exist so it can be watched—a living museum of what once was.

But symbolism cuts both ways. To a small but vocal segment of Afrikaners, Orania is a beacon. A place where they can speak Afrikaans freely, teach their history without filter, and raise families untouched by what they see as societal decay.

Controversy about Orania

To visit Orania—or even to study it—is to confront uncomfortable truths. It challenges the illusion that post-apartheid South Africa is wholly united. It exposes the lingering fractures, the spaces where the rainbow nation metaphor breaks down.

Orania is not just a town. It’s a mirror—showing us what happens when fear of change outweighs the promise of coexistence. It reminds us that reconciliation is not automatic. That integration is not inevitable. And that democracy, no matter how robust, will always be tested by the ghosts of history.

Whether Orania is seen as a cultural sanctuary or a racist enclave depends on where you stand. But one thing is certain: its existence forces South Africa—and the world—to keep asking the hard questions.

Leave a Reply