In modern Vietnam, stories of white-collar crime rarely lead to capital punishment. For this reason, the case of Truong My Lan stands apart in a way that few legal events in Southeast Asia ever have. Her case did not unfold quietly. It stirred debate in homes and offices across the country, unsettled regulators, and shook investor confidence. It also revealed how one individual could influence a major bank, move extraordinary sums of money, and place an entire financial sector under strain.

The events that led to her conviction were dramatic enough to gain attention throughout the region. Yet the story began in a modest part of old Saigon, long before luxury towers and international investors shaped the city’s skyline.

Early Life and Family Background

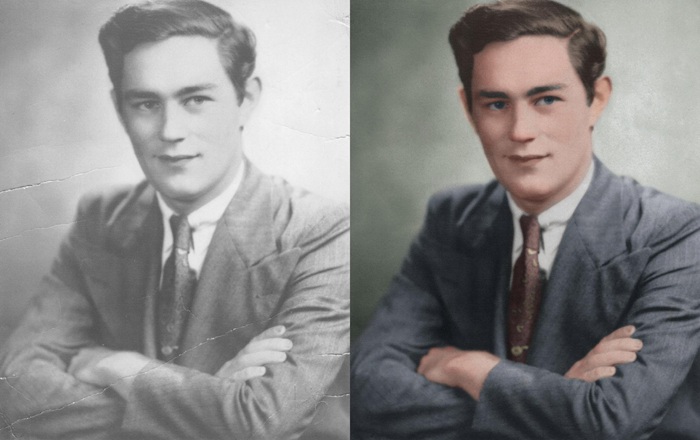

Truong My Lan was born on October 13, 1956, in a community of Teochew Chinese families who had lived in Saigon for generations. Her ancestors had come from the village of Gezhou in Shantou, Guangdong Province. Many of these families settled in a part of the city that people casually referred to as Little Gezhou. It was a crowded area, filled with small shops and market stalls where traders sold food, clothes, cosmetics, and household goods.

Lan grew up in this setting. Her childhood was shaped by the noise of vendors calling out prices, the steady flow of customers, and the familiar routines of a working family. She helped her mother sell cosmetics in the market. Her early life did not show signs of the enormous wealth and influence she would later gain. Yet people who knew her at the time described her as observant and determined. She understood the habits of buyers, the importance of relationships, and the rhythm of business in a growing city.

During the years that followed the end of the Vietnam War, the economy struggled. Markets operated with uncertainty and limited private enterprise. It was not until the government introduced the policy known as Doi Moi in 1986 that new possibilities began to open for entrepreneurs across the country.

The Beginning of Her Business Career

When economic reforms allowed private businesses to grow, Lan was ready to take advantage of the new environment. She moved from small retail work into real estate, which was becoming a promising field in Ho Chi Minh City. Many properties owned by the state were in poor condition, underused, or waiting for redevelopment. The legal framework was still evolving, and investors who understood the market could acquire valuable land at relatively low cost.

Lan began purchasing properties across the city. Her strategy was patient and consistent. She acquired land quietly, renovated older buildings, and developed new structures in locations that she believed would gain value in the future. This approach worked. As Vietnam opened more fully to foreign investment in the early 1990s, demand for commercial and residential projects increased.

By 1992, she had accumulated enough resources to establish the Van Thinh Phat Group. This company quickly became known for high-end real estate. It built hotels, office complexes, luxury residences, and shopping centers. Many of these projects occupied prime areas of Ho Chi Minh City. The company’s growth coincided with Vietnam’s rapid shift toward a more market-oriented economy. Foreign investors visited the city regularly, and new partnerships formed between Vietnamese businesses and international firms.

Lan’s public image rose with the expansion of her company. She was seen as a symbol of economic progress. While others struggled with limited capital or slow approvals, she developed large projects that shaped the appearance of the city. Her network expanded into government circles, financial institutions, and private corporations. This influence would later become a source of concern for regulators.

The Quiet Control of Saigon Commercial Bank

Although her real estate business was already significant, Lan’s most consequential decision involved the banking sector. In 2012, Vietnam’s financial system was under pressure. Several banks faced difficulties because of poor loan management and unstable investments. To avoid collapse, the State Bank of Vietnam approved a merger of three struggling institutions. This merger created Saigon Commercial Bank, commonly known as SCB.

On paper, SCB was formed to strengthen the financial system. In practice, the situation became more complex. Through a network of representatives and indirect ownership, Lan gained substantial control over the bank. She did not hold an official leadership position, yet she influenced decisions within the institution. Many loans issued by SCB were eventually tied to companies connected to her or managed by people acting under her direction.

Investigators later revealed that more than ninety percent of SCB’s loan portfolio was linked to her business network. This level of influence allowed her to move money between companies, acquire new assets, and finance large development projects without traditional oversight.

The Growth of a Financial Empire

Between 2012 and 2022, SCB operated in a way that gave Lan access to extraordinary sums. Authorities reported that she and her associates created hundreds of fraudulent loan applications. These applications allowed funds to be transferred to companies she owned or controlled. The numbers reached a scale rarely seen in banking fraud cases.

Court documents presented during her trial described the following amounts:

About 12.5 billion dollars in embezzled funds

About 27 billion dollars in misappropriated assets

Total controlled assets reaching as high as 44 billion dollars

To understand the size of these figures, consider that her embezzlement alone matched nearly three percent of Vietnam’s entire gross domestic product in 2022. Economists across the country expressed disbelief at the scale. Prosecutors noted that this case was far larger than previous corruption scandals in the region.

Authorities identified more than one thousand assets tied to her activities. These included high-value real estate in central Ho Chi Minh City, shares in multiple companies, and offshore holdings. Many of these assets have since been frozen while the government works to recover losses.

The Anti-Corruption Campaign

On October 6, 2022, Lan was arrested. Her arrest occurred during a national anti-corruption campaign led by the Communist Party of Vietnam. The campaign, often referred to by officials as the Blazing Furnace, targeted corruption in government offices, financial institutions, state-owned companies, and private businesses with strong political ties.

Her arrest had immediate consequences. Three SCB employees took their own lives within days of the announcement. Customers lined up outside bank branches in fear, seeking to withdraw their savings. The State Bank of Vietnam stepped in to stabilize the situation, injecting funds into SCB to restore public confidence. The atmosphere remained tense for weeks as people questioned the strength of the financial system.

The Trial and Sentencing

Lan’s first trial began on March 5, 2024, at the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court. There were eighty-six defendants, including her husband, her niece, and numerous former SCB executives. The scale of the trial required special arrangements. The courtroom was equipped with screens and translation services to manage the volume of documents and testimonies.

Those on trial included:

Her husband, Hong Kong businessman Eric Chu

Her niece, Truong Hue Van

Dozens of former SCB leaders

Officials from the State Bank of Vietnam

Inspectors and auditors from national agencies

Five SCB executives fled the country and were tried in absentia.

After more than a month of hearings, the court delivered its decision on April 11, 2024. Lan was sentenced to death by lethal injection for embezzling 12.5 billion dollars. Several co-defendants received life sentences. Others received lengthy prison terms ranging from three years to twenty years.

The verdict drew widespread attention. Vietnam had rarely sentenced women to death for financial crimes. The outcome reflected the gravity of the case and the government’s determination to send a strong message. Her legal team immediately filed an appeal.

The Second Trial and Additional Convictions

A second trial began on September 19, 2024. This time, prosecutors focused on money laundering and the illegal sale of bonds. They argued that Lan had moved approximately 4.5 billion dollars through domestic and international channels between 2012 and 2022. The transactions involved twenty-one companies within the Van Thinh Phat Group.

On October 17, 2024, the court found her guilty once more. She received a life sentence in addition to the earlier death penalty. The court noted that these charges confirmed the scale of her operations and reinforced the conclusions of the first trial.

The Final Appeal and the Possibility of Commutation

Her final appeal was heard in early December 2024. On December 3, the court rejected her arguments and upheld the death sentence. However, the law allowed for one remaining possibility. If she could repay seventy-five percent of the embezzled funds, estimated at about nine billion dollars, her sentence could be reduced to life imprisonment.

During her final statement, observers saw a different side of her. She appeared tired and emotional. She expressed regret and asked for more time to repay the funds. She described the situation as an accident, which was interpreted as an effort to gain leniency rather than an admission of guilt.

Her husband chose not to appeal his own conviction. Instead, he repaid the amount he was accused of laundering. His repayment led the court to reduce his sentence from two years to one year.

The Impact on Her Family

Lan’s family had once been regarded as one of the wealthiest in Vietnam. Their philanthropic efforts extended to several communities in China as well as Vietnam. Her daughter, Elizabeth Chu, born in 1994, lived mostly outside the spotlight and was reportedly managing restaurants in Hong Kong.

With Lan’s conviction, the family’s assets were frozen. Authorities continue to examine properties, corporate shares, and foreign accounts to determine how much can be recovered. Her niece, who had been close to her since childhood, admitted to creating numerous shell companies and helping secure 155 loans from SCB. The confession illustrated how deeply the scheme reached into her business and personal circles.

The Broader Consequences for Vietnam

The scandal damaged confidence in the banking system. It also exposed weaknesses in regulatory oversight. Vietnam had already invested considerable effort in improving financial transparency. The case revealed that further reforms were needed to prevent similar problems in the future.

The comparison to Malaysia’s 1MDB scandal was immediate. That case involved about 4.1 billion euros. Lan’s case surpassed it by a large margin. Economists described it as one of the most significant financial crimes in regional history.

The cost to the Vietnamese state is still under assessment. Losses from SCB, public spending to restore stability, and reduced investor confidence will continue to affect the economy for years.

A Legacy Marked by Influence and Collapse

Lan once dominated the real estate market in Ho Chi Minh City. Her company shaped major parts of the urban landscape. Investors believed in her projects. Government officials relied on her financial networks. Her influence reached far beyond business. It affected policymaking, banking operations, and international partnerships.

Today she lives in a prison cell. She is identified by a number rather than a title. Her future depends on whether she can recover enough funds to qualify for commutation. Her story remains a topic of discussion throughout Vietnam. People examine it not only because of the size of the crime, but also because it reflects deeper questions about governance, accountability, and the consequences of unchecked influence.

The case is now part of Vietnam’s legal and economic history. It serves as a reminder of how quickly success can collapse when transparency is missing and oversight is weak.